Thousands of Iranian emigrate every year to attend university abroad because most of them are afraid of what Iran’s future may hold. Parents want their children to study in a country with less conflict and a chance of a better life, away from Iran’s high unemployment.

Many graduates take up unfulfilling careers as “pseudo taxi-drivers”.

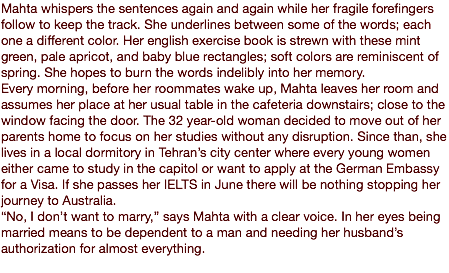

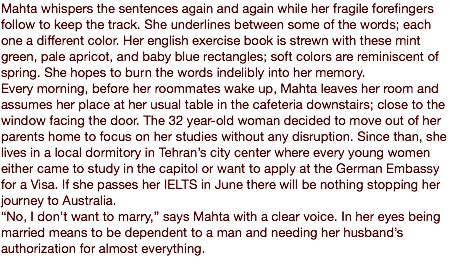

Both men and women are increasingly educated in Iran, while according to the Statistical Center of Iran, more than half of university students have been women since 2000, and the number reached in the next years.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) reports that more than 48,000 Iranian students were studying abroad in 2014 compared to 2008 when fewer than 27,000 Iranians were at foreign institutions.

Thousands of Iranian emigrate every year to attend university abroad because most of them are afraid of what Iran’s future may hold. Parents want their children to study in a country with less conflict and a chance of a better life, away from Iran’s high unemployment.

Many graduates take up unfulfilling careers as “pseudo taxi-drivers”.

Both men and women are increasingly educated in Iran, while according to the Statistical Center of Iran, more than half of university students have been women since 2000, and the number reached in the next years.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) reports that more than 48,000 Iranian students were studying abroad in 2014 compared to 2008 when fewer than 27,000 Iranians were at foreign institutions.